‘A few acres of snow’ — that was Voltaire’s contemptuous comment on France’s loss of its North American possessions as a result of the Seven Years’ War. Had France won the battle for the territories east of the Mississippi, world history would in all likelihood have taken a very different course. The world-shaking French Revolution might never have happened, nor would the United States of America have emerged as an English-speaking world power. The world would primarily speak French today.

Even today, on the surface, it may only be a matter of a few bits of snow and ice. With a population of just 60 000 souls. And yet it could once again be a turning point in world history: the final end of the post-war consensus that outlawed border shifts and put a stop to the territorial hunger of the great powers. Of course, there was no question of an end to imperial ambitions, but the borders established after 1945 and decolonisation proved to be surprisingly durable. Where multi-ethnic empires collapsed, territorial reorganisation generally took place along existing administrative boundaries.

Of course, other factors also played a role, as evidenced by the Serbian wars in the former Yugoslavia and, since 2014 and 2022 respectively, Russia’s war against Ukraine. However, these remained exceptions to the rule — and were largely condemned internationally.

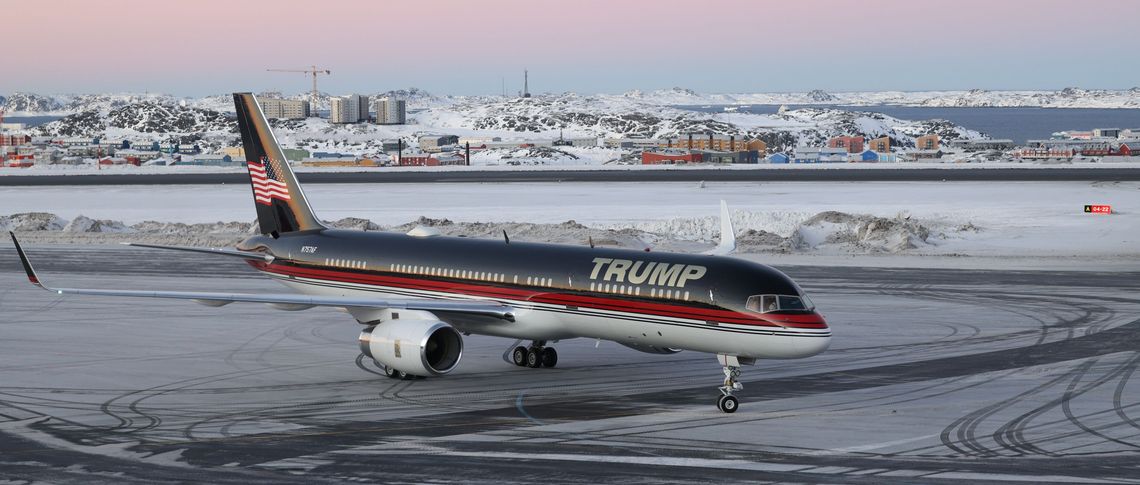

In 1990/91, a global coalition formed against Saddam Hussein’s hunger for land, and even most of the Jewish state’s allies reject Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem and the Syrian Golan Heights. Many states, though no longer a majority, still do not recognise the secession of the formerly Serbian Kosovo. Now, however, the US under Trump is openly reaching for Greenland. ‘For reasons of national security’, which is ridiculous given that American global and NATO supremacy already allows it to do as it pleases militarily there. If we are honest with ourselves, there is no way around the conclusion that Trump is purely interested in power politics, satisfying his hunger for land and gaining prestige. Imperialism, perhaps as a social media operetta, but in its purest form.

Acknowledging the new reality

‘With what right’ does Denmark exercise control over Greenland, asks Stephen Miller, chief adviser to the US president and his ideological attack dog, rhetorically. A flimsy question, because what border is 100 per cent legitimate? Name a state that was not historically based on robbery, murder and expulsion. Without land grabbing and massacres, the United States would not exist, but that is far from being its unique selling point. The consensus after 1945 was that questioning borders again, even where they were not always legitimate, would not heal past suffering but would produce millions of new cases. Greenland’s borders are a matter for the Greenlanders themselves and the Danes in the joint kingdom. No one of importance there has expressed a desire to change anything.

Meanwhile, the cries for help from Copenhagen are becoming increasingly panicked. The Social Democratic Prime Minister is appealing with unprecedented fervour to Washington to refrain from ‘its threats against a historically close ally’. Militarily, it is clear that the kingdom of six million would not stand a chance against the most powerful military machine in world history. If Trump really wants it, Greenland is his.

So it’s most likely just a question of price. That could be prohibitively high — but not if little Denmark is left on its own. Europe would have to pull itself together and finally acknowledge the new reality in Washington. For now, it is still operating according to the motto ‘what cannot be, cannot be’. The erratic in-chief in the White House must somehow be satisfied. Gestures of humility follow one after another, including embarrassing photos of joint visits to ‘Daddy’.

It is precisely the fear of losing the United States as a leading nation that prevents Europeans from actively working towards their own independence.

The rest of the world is astonished to see the extent to which the former masters of the world are now capable of self-humiliation. No matter how openly Washington signals that it considers Europe to be virtually degenerate and on the path to ‘civilisational suicide’, transatlanticism is so deeply ingrained in the minds of the political elite that any debate on ‘European sovereignty’ has so far been inconsequential.

It is precisely the fear of losing the United States as a leading nation that prevents Europeans from actively working towards their own independence. This fear drives them deeper and deeper into security dependence, including billion-pound contracts for the US arms industry, which chain Europe’s armies to Washington for decades. However, if the superpower becomes a threat, or even harbours political and territorial ambitions against Europe, a military alliance that binds Europe militarily to Washington no longer makes sense. Unless, of course, suicide is actually the goal.

The cowardice with which every move from overseas is praised against better judgement and against one’s own interests, every obvious violation of international law is glorified as necessary ‘dirty work’ or as ‘complex’, is not a realpolitik necessity arising from recognition of one’s own weakness. It actively undermines the principles that are the basis of one’s own existence.

As a reminder, a NATO ally is being threatened here. It may not feel like it, but this is different from the attack on Ukraine, with which Germany shares neither NATO nor EU membership. However, the principles at stake are the same: sovereignty, territorial integrity, the prohibition of land grabbing and border shifts. How are these principles to be defended in Ukraine when our own main ally is undermining them and turning them against us?

Weighing out ambitions and potential

It is fear of Russia that chains us to the erratic United States. However, a realistic assessment of the balance of power must conclude that Russia’s drive for expansion is severely limited. The army, which has been stuck in the mud of Donetsk for almost four years, is unlikely to march on Warsaw or Berlin tomorrow. Economically, Russia remains a quantité négligeable. Ideologically, too, Putin has never declared such a goal. He is concerned with restoring the triune Slavic nation. The threat to Ukraine is real, and in theory also to Belarus.

America, however, has more far-reaching capabilities and goals. Washington has its sights set on dominance over the entire Western hemisphere. In qualitative terms, this is no different from Russia’s claim to dominance over the post-Soviet ‘near abroad’. The right of Latin Americans to self-determination counts for little. However, they articulate their opposition much more resolutely. Unlike the Europeans, who remain paralysed by fear, they are by no means prepared to become vassals.

‘No one can stop us,’ Trump commented on the kidnapping of the Venezuelan potentate. That Greenland would be the end of it is by no means certain. As we all know, appetite comes when you eat. The president has already spoken at length about Canada, which he considers to be ‘the 51st state’. A glance at the map is enough to see that, after the annexation of Greenland, North America’s largest country in terms of area would be surrounded on three sides.

Anything goes is increasingly becoming the motto of the geopolitical present.

Trump did not invent the idea of almost complete American domination of the North American continent. Manifest Destiny was never limited by the 49th parallel, along which most of the American-Canadian border runs. Trump is satisfying desires that have existed for a long time. Following imperial logic, Canada would be quite ‘swallowable’ for the United States, which is ten times larger. In terms of population, culture and history, Ukraine is a much bigger bite for Russia than Canada would be for the US.

‘Those few acres’ of Greenlandic snow thus open Pandora’s box for far-reaching changes. Not only would this legitimise Russia’s grab for Ukraine in retrospect. The entire rules-based order – even in its minimal consensus against border changes and wars of aggression – would be passé. The result would be what Marc Saxer calls the ‘wolf world’: an order in which every state looks out for itself. The period from 1945 to 2025 would have been an interlude, let’s call it the UN order. Before and after, the traditional disorder would once again prevail, albeit with the special feature of nuclear armament, whose appeal would increase exponentially for any country that did not want to find itself on the menu of others. No one can say how long this would last. The assumption that Europe would be spared is illusory.

This dystopian abyss is not yet a complete reality. However, it is no longer a completely crazy vision of the future — as one would have had to argue a year ago. ‘Anything goes’ is increasingly becoming the motto of the geopolitical present. The EU, the very embodiment of the declining rules-based order, stands as the last bastion of stability.

China and Brazil have shown that the most successful way to deal with Trump is not to let him intimidate you.

Its members must shake off their paralysis of fear. Trump speaks the language of power, and it is precisely this language that Europeans should finally learn. The price of US action against Danish Greenland must be driven up. A year ago, Paris had already raised the idea of joint troops on the island. The reaction from Berlin and London? Rejection. Yet this is precisely the path that should be taken: to make it clear to Washington that any move against Greenland would also be a move against Germany, the United Kingdom, France — and possibly Poland and Italy. ‘One for all, and all for one. Otherwise, we are finished’, tweets Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, alluding to Europe.

Jeremy Cliffe from the think tank European Council on Foreign Relations recommends ‘tariffs, taxes and bans on US companies’, selling off US government bonds and closing American military bases. There are certainly means of exerting power beyond purely performative Twitter solidarity with Denmark. The point is not so much that all of this must necessarily be implemented. Simply taking a look at Europe’s arsenal of weapons could be enough to influence the volatile debate in Washington. China and Brazil have shown that the most successful way to deal with Trump is not to let him intimidate you. Ultimately, he is not a Putin with an iron will, nor is he an ideologue, but rather a dealmaker. Showing off, not perseverance, is his trademark.

All this requires, however, that Europe take the threat seriously and evaluate its means of power (and their expansion) now. America’s drift demands European independence and sovereignty more than ever. It is to be hoped that the course for this will be set now, while the Dannebrog still flies over Greenland, and not only after it has been caught up.