The style of US politics makes people in Europe raise their eyebrows in awe and wonder. The vibrant rhetoric, exuberant debates and overall intensity of the campaigns find nothing even remotely comparable in any European country. However, a closer look reveals that Europe today faces problems similar to those in the United States.

The populist tide and political polarisation are clearly visible across the old continent. The heat of political competition goes hand in hand with the growing alienation of the political mainstream from the voter base. Progressive parties on both sides of the Atlantic seem to be losing their charm as they struggle to mobilise for victory. So perhaps the US and Europe have more in common than we think?

Economic decline fuels the populist tide

Democratic decline is particularly visible in regions that have experienced structural mismatches resulting in unemployment, deteriorating living standards and depopulation. Deindustrialisation has left scars and ruptures in the social fabric of the industrial heartlands of North America, such as the former Steel Belt, European coalfields like the Ruhr or north-east England and the former Eastern Bloc after 1989. Repeated crisis, uncertainty and change fatigue lead to a disconnection from mainstream politics.

In East Germany, for example, a large majority still feels like second-class citizens. Across the EU, just over half are satisfied with the way democracy works. Only 23 per cent of all Americans trust the government. Faith in democracy is declining, especially among the younger generations, while – and this is particularly worrying – anger and exhaustion are most common among those who are politically engaged.

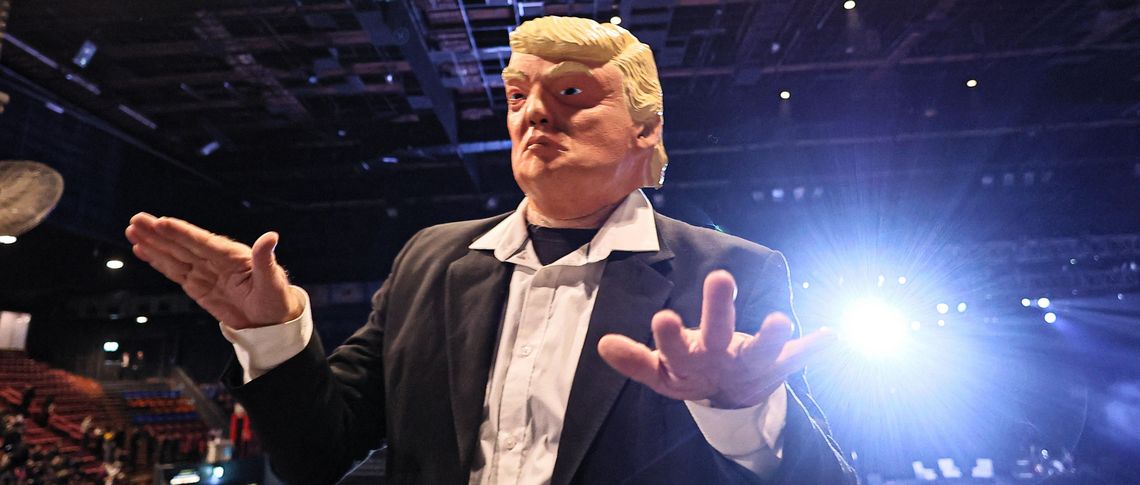

Estrangement and frustration are powerful feelings. This intoxicating mix creates a perfect storm for different kinds of populism to emerge. Rising populist sentiment haunts both the right and the left side of the political spectrum. Viktor Orbán and Jarosław Kaczyński triumphed in Hungary and Poland, offering illiberal-conservative narratives. In Germany, the left-wing BSW has embraced a pacifist populism that feeds on war anxiety. The right-wing populist German AfD and Austrian FPÖ are exploiting fears of migration. In Italy, Georgia Meloni built support around her persona: coming from the people, serving the people. Finally, in the United States, Donald Trump combines several threads, in the end making it all about himself, calling the critical media ‘horrible liars’.

The electoral success of populists proves that populism is a powerful tool for voter mobilisation. But the fact is: elections are won by appealing to the broadest voter base possible. All centrist parties face the same dilemma: how to better connect with the people without falling into the populist trap? We suggest a strategy of drying out the root causes of populism through smart regional policies, a new politics of emotions and depolarisation by emphasising common interests rather than playing up differences.

Tackling regional disparities

Political discontent is directly linked to local living standards. Rural areas and post-industrial towns have suffered depopulation as a result of past transformations, leading to anxiety and despair. Those who stay in structurally weak regions and dysfunctional cities are fed up with bumpy roads, lack of access to affordable healthcare or crumbling schools. Ongoing brain drain, fuelled by a sense of relative deprivation when comparing home to other places, causes anger and frustration despite strong local identities and affection for the region. Sometimes the feeling of being left behind leads to nostalgia, isolation and intolerance, instead of embracing new ideas, people and opportunities. Once in place, it is difficult to break out of this vicious circle. The ‘geography of discontent’ and the urban-rural divide are creeping across the United States and Europe.

Cohesion policy is only one side of the coin. Connecting with voters on an emotional level is the other.

Tackling regional disparities is therefore an essential political objective to reconnect with voters. Well-designed regional policies can strengthen our democracies and curb populist resentment in the medium and long term. And this objective is popular, too. A recent poll conducted by Das Progressive Zentrum found that 76 per cent of Germans would support more federal spending to strengthen left-behind regions. It is therefore no coincidence that President Joe Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022, thus investing billions in declining regions.

Yet, cohesion policy is only one side of the coin. Connecting with voters on an emotional level is the other. Every region has a unique history of prosperity and decline. Building a positive identity requires understanding the past in order to link it to the future. Just like in Detroit, where the success of the ‘Motor City’ is being transformed into the aspiration of a tech city. ‘Detroit never left’, they write on T-shirts there. Or in the North East of England, which takes pride in its prosperous coal mining past, celebrating its work ethos and solidarity. Or in East Germany, where a new identity is emerging, that combines the socialist past, the harsh transition period of the 1990s and the accomplishments of East Germans in the unified Germany.

Connecting the past with the future should be accompanied by a stronger focus on local solidarity. Deutschland-Monitor, a major annual opinion poll on political attitudes in Germany, found that many people miss solidarity in society in general — but the majority find it still exists in their communities. Progressives need to talk about this discrepancy and focus on the prerequisites for local solidarity.

From bad populism to positive communitarianism

Tackling regional disparities and strengthening local solidarity are potential remedies for populist sentiments. At the same time, all democratic parties should reflect more carefully on how to deal with issues that are regularly exploited by populists: migration, climate, the pandemic, worldview issues. Is shying away from these topics the right strategy? In her campaign, Kamala Harris proactively addressed issues such as migration and inflation, despite the belief among some voters that former entrepreneur and ex-president Trump would have more leverage on these matters.

Mainstream politicians have every reason to be more self-confident. They should remember that while fringe positions attract attention, most people still belong to the ‘relatively stable, non-ideological centre’. This majority has coherent views on core issues such as climate change and injustice (negative), as well as migration and diversity (positive with reservations). They do not want a polarised discourse; on the contrary, they fear it. Therefore, good politics of the centre must talk more about common values, shared views and a united, solidaristic society in which people rely on each other.

Daring to express more positive emotions such as solidarity, aspiration and hope is the answer. Hope and change were central to the successful Obama campaign. Today’s Harris-Walz campaign is all about ‘turning the page’ on chaos and hate. Don’t shy away from big political challenges. Just frame them differently from the populists. The secret sauce is to build a convincing, inclusive and positive narrative about the future. Migration is good for the economy and for reviving local communities. Action against climate change stimulates technological progress. Protecting civil liberties gives everyone the right to live according to their values, whether conservative or progressive.

Populists instrumentalise these vital issues for immediate political gains. The progressive political response should be to build bridges, not walls. Common interest is not only reinstalling the sense of community but also making sure basic needs are sufficiently met and equal chances are provided regardless of geographical location. Positive stories about the future will only be convincing if no one is left behind.