More than many other Central American countries, Honduras has been under the direct influence of the United States since its independence in 1821. From the imperial adventurers around the filibuster William Walker, to the banana enclaves of the United and Standard Fruit Companies, and finally to the American-drafted, formal two-party democracy of the 1980s, the ‘big brother’ from the north has always exerted its influence openly. As was the case in 2009, when the left-wing president Manuel Zelaya was deposed by the military. Ostensibly because he was aiming for an unconstitutional second term; in reality, because he had dared, as a member of the country’s old-established elite, to challenge its unrestricted power.

This dramatic event was followed by twelve years of popular resistance, especially by trade unions, indigenous organisations, student unions and feminist groups, against what soon became known as the ‘narco-dictatorship’ of the right-wing Partido Nacional (PNH), which remained formally confirmed in office three times through elections. Out of this broad resistance movement emerged the party Libertad y Refundación (LIBRE), committed to democratic socialism. Founded by Zelaya himself, who still serves as a moderator among its many factions, LIBRE achieved a landslide victory in the 2021 presidential elections with his wife Xiomara Castro at the helm, winning over 50 per cent of the vote.

Now, four years later, the sense of disappointment is almost indescribable. Certainly, the signs before the election were far from positive: too many reform projects failed due to the lack of a congressional majority; too many times the party’s radical base was disillusioned by rotten compromises with the old elite; too often LIBRE had to face the reality that it too was not free from corruption or from ties to the country’s all-pervasive drug cartels. The party was evidently ill-prepared for the famous ‘labours of the plains’. Until the very end, it failed to find a real way to implement its political vision within a state whose institutions had, since its founding, served almost exclusively to enrich the national elites, and which had been used as an ‘aircraft carrier’ for US interventions in the region’s conflicts and revolutions. It never succeeded in establishing its own narrative against the negative coverage of the conservative media landscape. And yet, the scale of the electoral defeat is scarcely expressible in words. Not only were the streets of the capital, Tegucigalpa, and the industrial metropolis San Pedro Sula empty on the Monday after the election; from the party base and civil society one hears nothing.

American pressure

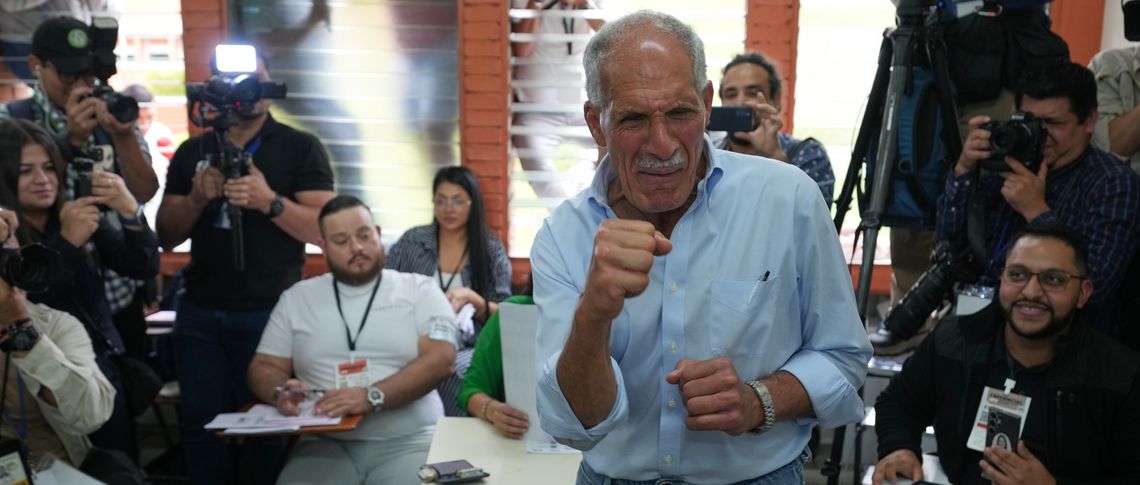

Triumphant instead is the old order. By Tuesday, the PNH and its candidate Nasry Asfura were narrowly ahead of the self-proclaimed anti-corruption crusader Salvador Nasralla, who this time stood for the centre-right Partido Liberal (PLH). They were already pressing for recognition of their victory, despite half of all votes still to be counted. Both parties represent the old two-party system, with the PNH positioned somewhat further to the right than the PLH. Both are historically anti-communist and pro-American. The former TV presenter and populist Nasralla had last stood in 2021 with his own party, Salvador de Honduras, in coalition with LIBRE.

During the campaign, both successfully stoked fears that Honduras might become another Venezuela or even Cuba. They warned the international community, resonating widely, of an authoritarian coup by the government. And they completely obscured how, under the last PNH government, Honduras had degenerated into a self-service shop for globalised capitalism: entire regions were ceded to foreign investors as so-called development zones. These produced neither development nor jobs, but plenty of tax exemptions for Peter Thiel and other proponents of techno-feudalism. Corruption and drug trafficking reached unprecedented levels, particularly under the last PNH president, Juan Orlando Hernández. He was extradited to the United States under the LIBRE government and sentenced to 45 years in prison for drug trafficking. Only two days before the election he was pardoned by Donald Trump. Trump also promised generous US support should ‘his candidate’ Asfura win. If not, he threatened tariffs and deportations. This is, to be sure, the new ‘normal’ of US foreign policy in what it regards as its backyard. But more than a million Hondurans live abroad, most of them in the United States. Their remittances are indispensable for the Honduran economy.

By law, the electoral authority has up to 30 days to announce the final results, even though Donald Trump, among others, is pressing for speed.

None of this seems to have mobilised support for LIBRE. After 84 per cent of the votes were counted, Asfura and Nasralla were neck and neck at around 40 per cent each. As of Thursday morning, Asfura again leads, by only 14 000 votes. Rixi Moncada, LIBRE’s proposed defence minister, trails far behind in third place with around 19 per cent. There is no run-off in Honduras; the candidate with the most votes is declared elected. Voter turnout appears to be significantly lower than in 2021, likely dropping from over 68 per cent to around 40 per cent. Reliable data on voter movement or motivations is unavailable in Honduras, but it appears that the PNH maintained its absolute vote count and thus greatly increased its share. LIBRE supporters either stayed home or placed their trust in Nasralla, who at least superficially managed to present himself as an anti-establishment candidate.

The campaign itself was already overshadowed by mutual accusations of manipulation. The temporary 24-hour interruption in vote counting does little to boost confidence in the authenticity of the results. LIBRE has cautiously conceded defeat while simultaneously raising fresh allegations — mainly against the PNH, which was already known for electoral fraud during its time in power. Contrary to all fears voiced by the international community, a coup by LIBRE is not to be expected, and there were no major disturbances on election day. By law, the electoral authority has up to 30 days to announce the final results, even though Donald Trump, among others, is pressing for speed. Despite his earlier friendship with Trump, Nasralla is currently taking a firm stance against this interference from the north. No party is likely to secure a majority in parliament. The latest figures show 50 seats for the PN, 40 for the PL and 34 for LIBRE, out of a total of 128.

Former president Zelaya will play a decisive role. He seems to be the only person with sufficient integrative power to unite the diverse Honduran left.

Thus LIBRE will play no part in the outcome of the presidential election — a historic opportunity to profoundly transform Central America’s poorest country has, for now, been squandered. What happens next will depend on how the party and broader movement analyse the defeat once the initial shock has passed: LIBRE appears to have been reduced to its core electorate, which at nearly 20 per cent is not insignificant. Will this be seen as a basis for a new beginning, or will the internal fractures within the party’s broad base now come to the fore even more clearly?

Former president Zelaya will play a decisive role. On the one hand, he seems to be the only person with sufficient integrative power to unite the diverse Honduran left. On the other hand, and this is also shown by the poor result of the respected but not particularly loved policy expert Moncada, LIBRE urgently needs new, charismatic figures if it is to challenge the two-party system again. At least, many new deputies will presumably sit in Congress, and despite the current disappointment, LIBRE seems far more rooted in the country than many other progressive projects in the region. Despite the bitter defeat, one can only hope that opposition also brings opportunity, and that a new awakening for the left can emerge — independent of Donald Trump’s wishes.