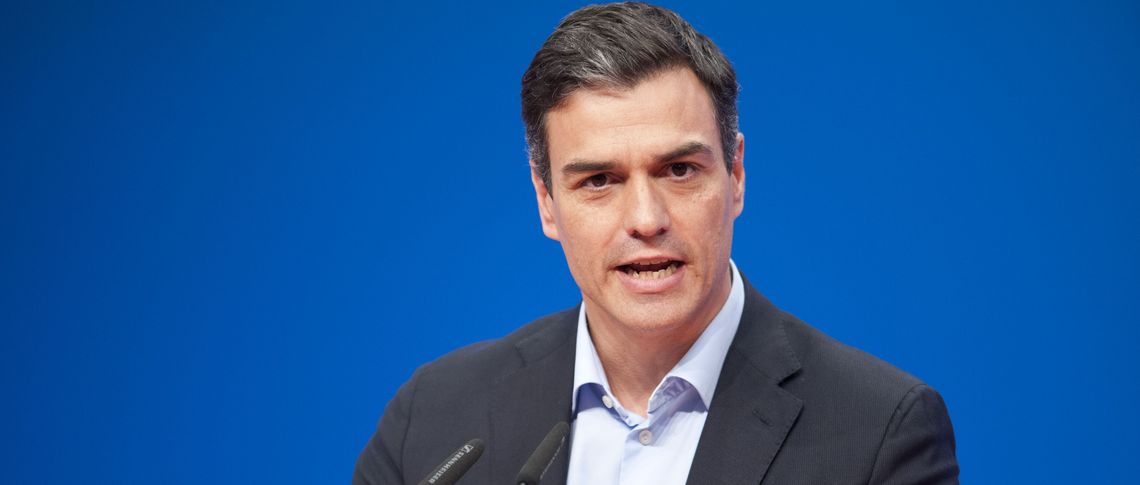

Just days before Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez attended a democracy forum in Latin America, the European Commission rendered its verdict on his controversial Amnesty Law, which pardons or halts the prosecutions of hundreds of politicians and others involved in the failed bid for Catalan independence between 2012 and 2023. The law failed the democracy test.

The Commission not only determined that the law meets the definition of a proscribed ‘self-amnesty.’ It also questioned whether the policy was even meant to serve the public interest, or whether its purpose was to secure a political pact to keep Sánchez in power. Having failed to win a parliamentary majority, Sánchez desperately needed the backing of separatist parties to remain in office. His government has no credibility when it claims that amnesty was necessary to promote political reconciliation and institutional normalisation between Catalonia and the Spanish state. Until the electoral math turned against his Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), Sánchez himself opposed amnesty.

Breaking with democratic tradition

Sánchez’s manoeuvre sparked widespread criticism, not only from the opposition Partido Popular (PP) – which denounced it as a backdoor constitutional change – but also from within his own party. Felipe González, Spain’s longest-serving post-Franco prime minister, accused the current PSOE leadership of squandering the party’s longstanding social-democratic legacy – and all for a ‘purely personal need to cling to power.’

Moreover, Sánchez broke an unwritten political norm in a country afflicted by separatist nationalisms: one should never base a premiership on support from parties that fundamentally reject the legitimacy of the Spanish state.

The response to Sánchez’s conduct is a far cry from the enthusiasm that produced his unexpected victory in the 2023 snap election. Liberals across Europe and beyond hailed that outcome as a triumph for democratic centrism and ‘a victory for common sense,’ not least because it kept the far-right Vox party out of power. But those celebrations now look premature.

On top of the Amnesty Law, Sánchez has also appointed political loyalists to autonomous public entities, marking another departure from Spanish democratic traditions. The independent think tank Hay Derecho now warns of growing partisanship in key institutions, noting that professional standards are being eroded, and institutional checks and balances significantly weakened.

Sánchez has also targeted the media, accusing some outlets of harassment and of scheming to undermine his government.

The Bank of Spain is a prime example. For the first time, a sitting minister, José Luis Escrivá, was tapped to govern it, breaking the norm that appointments to the bank’s principal positions should command support from both the government and the opposition. Worse, the bank’s most recent report under Escrivá’s tenure conspicuously offered no analysis of the contentious pension reform that he himself led as minister. Such omissions inevitably undermine the bank’s credibility: although it is not a pension regulator, it has long been treated as an authoritative voice on such issues.

At the same time, the government named Dolores Delgado (a former justice minister) as Prosecutor General and then retained her successor, Álvaro García Ortiz, despite a censure for abuse of power and a pending criminal probe, further casting doubts on these institutions’ true autonomy.

Or consider the case of the Center for Sociological Research (CIS). A mostly technical research institution traditionally headed by non-partisan figures, its neutral reputation has been compromised by the appointment of José Félix Tezanos, a longstanding PSOE activist. His tenure has been marred by accusations of partisanship and allegations of manipulating polling data to overstate support for the ruling party.

The list goes on, and those institutions that have escaped undue politicisation have drawn Sánchez’s ire. Following allegations of corruption against his wife and brother, Sánchez, perhaps hoping to mobilise his base, publicly criticised the justice system and even accused judges of colluding with the PP to ‘harass’ his government. He has also targeted the media, accusing some outlets of harassment and of scheming to undermine his government.

Given global political dynamics, Europe’s defence of liberal values is more critical now than ever.

In How Democracies Die, the Harvard University political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt argue that modern democracies rarely collapse through violent coups; rather, they erode from within when elected leaders undermine the institutions that brought them to power. The process is usually slow-moving and undetected until it is too late, because it mostly falls within the boundaries of legality.

While democratic backsliding in Latin America is known to come both from the right and the left, in Europe, it has traditionally been associated primarily with right-wing governments. As a result, Sánchez, a staunch EU advocate who leads Spain’s traditional centre-left party, tends to get the benefit of the doubt.

And yet, in his seven years in government, he has repeatedly flouted Spanish democracy’s unwritten norms and sought to co-opt or weaken institutional checks on the government. Such behaviour suggests that Sánchez has become fixated on retaining power at any cost, and grown increasingly uncomfortable with institutions he does not control. Given the initial reactions to Giorgia Meloni’s rise to power in Italy, Sánchez’s conduct almost certainly would have already raised serious alarms had he not been seen as a left-wing liberal who has savvily held back the far right.

Given global political dynamics, Europe’s defence of liberal values is more critical now than ever. But this defence must account for risks arising from within. As Sánchez’s behaviour suggests, legitimate fear of democratic erosion from the right should not distract from similar threats on the left.

For a different view on this debate, see the article by José Montilla Aguilera ‘Spain’s real trial’.