China is a growing presence in the Middle East. The region has long been of interest to this industrial powerhouse — not just as a source of energy and a growing market for its own products but increasingly for geopolitical reasons too. So, should Europe be worried about this interest in the region closest to it? Perhaps less than some think. Setting paranoia aside, an objective assessment shows that, to date, China has not sought to disrupt.

Perhaps the key turning point came in March 2023 when, to the surprise of many observers, representatives from Iran and Saudi Arabia announced a rapprochement agreement in Beijing. China’s first foray into regional security, it was communicated on the world stage as marking the start of the country’s Global Security Initiative (GSI). Here was China, which the West has long derided as a free-rider in security policy matters, presenting itself as the guarantor of a deal between the two great rivals for regional hegemony.

In Beijing, international relations are always viewed through the prism of its rivalry with Washington.

Beijing’s aim was to ensure stability in the region — a not entirely selfless objective; after all, the People’s Republic gets almost half its crude oil and around a third of its imported gas from Middle Eastern countries. A war in the region, which would threaten the free movement of sea freight through the Strait of Hormuz, a key pinch point for shipping, would be a strategic nightmare for China’s energy-hungry economy. At the same time, Beijing’s mediation bolstered its credentials as an ideologically neutral peacekeeper, one evidently capable of bringing all the protagonists to the table – an ability that the US, objectively the region’s dominant military power, increasingly seems to have lost. In Beijing, international relations are always viewed through the prism of its rivalry with Washington.

Maintaining a careful balance

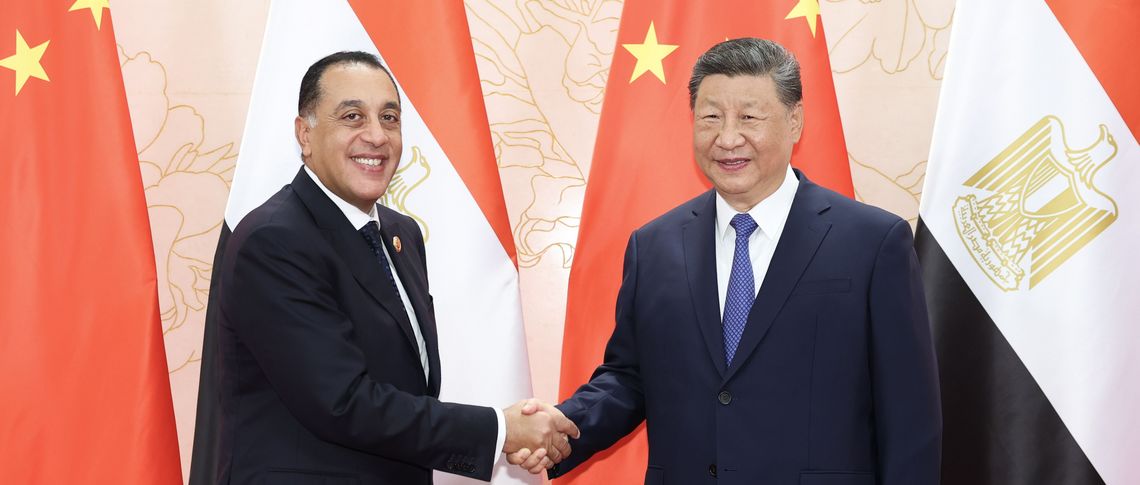

The Middle East’s growing importance is also illustrated by the fact that four of the six countries originally invited to join the BRICS+ bloc are from the region, an expansion that serves as a geopolitical complement to China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. The invitations cut across ideological boundaries, encompassing key US ally Egypt and the oil-rich kingdom of Saudi Arabia as well as the US’ arch enemy Iran. When it comes to the region’s conflicts, Beijing is pursuing a considered policy of non-partisanship, aiming to maintain good and balanced relations with all nations. Despite its foray into regional security, it is not seeking to provide iron-clad security guarantees for any one party.

This is the key difference between it and the United States. China is making cautious overtures towards the region — albeit with a clear objective of not adopting the US’ interventionist approach. It only wishes to get involved in situations where – as with the Iran-Saudi deal – there is a positive regional consensus. Beijing is taking great pains to avoid polemical statements, something Iran discovered during the Twelve-Day War; despite its membership of BRICS and of the equally China-dominated Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), its embattled leaders were offered little more than warm words. Militarily, the Islamic Republic was left to its own devices.

For China, the Middle East remains a secondary strategic priority, despite its growing involvement in the region.

That doesn’t mean that Iranians hold the People’s Republic in low esteem. As an emerging global power, China may not be one for militarily rash foreign policy escapades, but it still has a fundamental interest in the stability of the Iranian regime. Despite ever tougher America sanctions, it continues to import Iranian crude oil, thus providing a crucial economic lifeline that is keeping Tehran above water. From Beijing’s perspective, Iran remains a reliable supporter when it comes to establishing a post-American world order. Additionally, the relationship is so asymmetric that China also benefits economically thanks to particularly cheap oil imports. In future, Iran, hitherto sceptical about Chinese military technology, could even develop into a market for Chinese arms. After all, Tehran urgently needs to rebuild its air defences.

All this would need to happen without unsettling the economically far more powerful Arab Gulf states. Beijing is thus apparently pursuing a strategy of seeking to damage the US, without itself arousing suspicions within the region.

That Washington’s much-vaunted ‘Pivot to Asia’ hasn’t taken off is in large part down to the fact that the US has got bogged down in the quagmire of Middle East conflict and has, since 2022, also been tied up with Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine. From a Chinese point of view, these are far from unwelcome developments. For China, the Middle East remains a secondary strategic priority, despite its growing involvement in the region. Beijing shows little desire to join in with Western-led initiatives, be it against the Houthis’ blockade of Red Sea shipping or Iran’s nuclear programme.

From Gaza to the Global South

There is a historical precedent here. Back in 2001, the US was ready to adopt a significantly more confrontational approach towards China — until a Saudi-born terrorist, Osama bin Laden, ensured the US’ strategic focus would lie elsewhere for the next two decades. While the US was pursuing its ‘War on Terror’, the People’s Republic was able to complete its rise to industrial superpower. China, you could say, was one of the big winners of this ultimately misguided war.

There is one exception to China’s policy of non-partisanship in the region: Israel. Relations with Tel Aviv have significantly worsened since the conflict between Hamas and Israel began in October 2023. Prior to that, Beijing had seen it as very much in its interests to maintain good relations with America’s closest regional ally, regarding Israel as an esteemed high-tech partner — that esteem was also reciprocated on the Israeli side. In 2015, a Chinese consortium thus won the contract to operate a container terminal at the key port of Haifa, though the Israeli government subsequently curtailed China’s involvement following massive pressure from Washington, the city being a key port of call for the US Sixth Fleet.

Since the war broke out, Israel’s political room for manoeuvre has become even more constrained. Tel Aviv’s extreme military and economic dependence on Washington likely persuaded Beijing to no longer pay much heed to Israeli interests, not least because the grievous war crimes that have defined its campaign in Gaza give China a welcome opportunity to call out Western double standards and hypocrisy.

Unlike Western nations, Beijing doesn’t officially regard Hamas as a terrorist organisation.

They allow Beijing, self-appointed champion of the Global South, to take a stand against the ‘rules-based world order’ espoused by the West — arrogantly so in Chinese minds, which see it not as an expression of universal values but merely as a cover for Washington’s geopolitical interests. In response to these Western-defined rules, China has called for what its leader Xi Jinping has called a ‘new era of global governance’, one that moves away from competing blocs and unilateral power politics and affords the Global South a greater say.

In Chinese state media, the war in Gaza has been covered far more extensively than that in Ukraine, while on social media, generally subject to strict controls, the predominantly pro-Palestinian public has been given largely free rein to express its anger. Domestically, Gaza has evidently served to reinforce the country’s image of itself as the leading champion of the Global South.

China also briefly attempted to act as a mediator: in summer 2024, it invited representatives from 14 Palestinian parties, including Hamas, to Beijing. Presented by foreign minister Wang Yi, the resulting ‘Beijing Declaration’ on forming a unity government, however, proved to be overly ambitious given the political realities. Unlike Western nations, Beijing doesn’t officially regard Hamas as a terrorist organisation. In the context of the ICJ case against Israel brought by South Africa, the Chinese representative stressed that the Palestinians had a right to use force to resist the Israeli occupation, a widely held view in the Global South.

Israel is accused of defining its own security exclusively in terms of the total subjugation of others — an approach that is diametrically opposed to Beijing’s stability-focused vision for the region.

What bothers China significantly more than the simmering, decades-long Middle East conflict is the Israeli policy of aggression in the widerregion, which it regardsas extremely disruptive. Israel’s bombing of various foreign states, culminating in its attack on Qatar in early September — crosses multiple red lines for the People’s Republic with its concern for sovereignty and territorial integrity. Israel is accused of defining its own security exclusively in terms of the total subjugation of others — an approach that is diametrically opposed to Beijing’s stability-focused vision for the region. At the same time, this aggression is an open invitation for China to accuse the West of double standards, given its condemnation of Russia’s actions.

Although it has responded with what by Beijing’s standards are unusually strong words, no further measures have been taken. China has neither downgraded its diplomatic relations with Tel Aviv nor threatened to impose sanctions. At just a few million euros, its contribution to the humanitarian aid effort has been modest. Once again, Beijing is pursuing a cost-effective strategy of harvesting low-hanging fruit rather than getting embroiled in something that might ultimately have significant long-term costs.

‘Don’t do stupid shit’

Does that make China a free-rider? Not necessarily. It’s more that it is simply making a hard-headed political judgment call — in the knowledge that those who criticise China’s limited involvement would be even more sceptical were the People’s Republic to play a more proactive role.

What is the upshot? Beijing’s engagement with the Middle East has so far been fairly undisruptive. Its overtures have been cautious — it hasn’t gone marching in with much fanfare. Unlike the US in the neocons’ heyday or under the current regime with its unconditional support for Israel, China has shown no desire to ideologically reshape the region. Instead, this rising superpower is focusing more on promoting stability and remains well aware of its limited experience and its comparative lack of know-how. ‘Don’t do stupid shit’ was how Barack Obama once summed up his foreign policy doctrine. It’s a maxim that seems to perfectly encapsulate how Beijing has hitherto approached the Middle East.

All this means a little realism is required in the West, and in Europe in particular. Beijing is not using its power to turn the region against the West. Given its own Muslim minority, China is extremely wary about Islamism. In stability terms, it’s certainly possible to identify common interests. The Iran-Saudi deal, heralded as a great success in Beijing, might well have prevented the Twelve-Day War from spreading to Arab Gulf states. China thus helped to rein in Iranian hotheads — even at a moment of existential weakness for their country. This, too, was in Europe’s interest.

The invitations China extends to European nations are, of course, also designed to thwart any overly cosy partnerships with the US.

Realism, however, also means having no illusions. China’s regional technology transfers – be it for smart-city projects or in AI – are not value-neutral; should be seen in the context of the People’s Republic’s politics. And realism should tell us that, as long as relations between China and Europe remain strained, Beijing is not going to help the West out of a scrape by joining any all-Western initiatives.

The invitations China extends to European nations are, of course, also designed to thwart any overly cosy partnerships with the US. There’s little point getting exercised about such a strategy however. Brussels and Washington are themselves not always on the same page — under Trump, this is truer than ever. Europe would do well to learn from regional powers elsewhere. The new multipolar world doesn’t necessarily pose a threat, either due to instability or a loss of influence; in fact, it presents an opportunity for Europe to shape global affairs — if it wants to, that is.