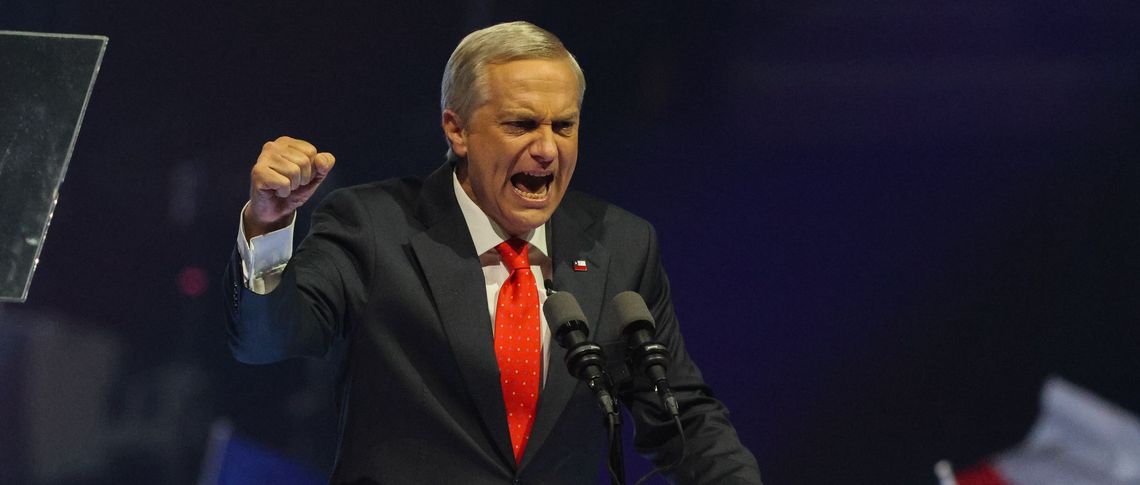

More than 50 years after Augusto Pinochet’s military coup, José Antonio Kast, a president who has neither distanced himself from the dictatorship nor credibly questioned its authoritarian traditions, is taking power. The son of a Wehrmacht officer and NSDAP member won the runoff election with 58.2 per cent of the vote against communist candidate Jeannette Jara, whose 41.8 per cent is more than a mere setback: it marks the end of a progressive project that has lost its majority. The victory is clear, comprehensive and nationwide: Kast won in all regions of Chile and in 312 of 346 municipalities, exceeding the 50 per cent mark in 78 per cent of polling stations. Jara was only able to win over voters in a few areas, such as Juan Fernández. This distribution underlines the fact that Kast is not only the winner of the election, but he has also managed to unite a genuine national majority behind him.

Initial analyses by age and gender show a clear base for Kast: he dominated in four out of six demographic groups, particularly among men between the ages of 35 and 54 (70 per cent) and women in the same age group (62 per cent). Young men under 35 and older men over 54 also supported him by a majority. Jara only scored points with young women and women over 54, while she did not achieve a majority among men. The data makes it clear that Kast has a broad base across age and gender groups — an alliance of uncertainty, anger and the promise of a firm hand.

Kast’s success was not only a reflection of his own popularity, but also the result of the consolidation of right-wing votes. The preliminary analysis suggests that around 55 per cent of Franco-Parisi voters chose Kast, while Jara won around 25 per cent of Matthei’s supporters.

For parts of Chilean society, the election of a communist as president was fundamentally inconceivable.

This strategic consolidation on the right was contrasted by the centre-left candidate, who failed to significantly expand her voter base. The increase in invalid and ‘blank’ votes, especially among those under 35, indicates dissatisfaction with both candidates and potential areas for political renewal but was much lower than feared.

The result is not directed solely against Jara, but above all against the progressive government that has been in power in recent years. Although she distanced herself from the government several times during the election campaign, she was considered its most successful minister; a large part of the population did not believe her separation from it. The security crisis, corruption scandals and the failure of the constitutional process had permanently shaken confidence in politics and, in particular, in the progressive camp. Added to this is a factor that should not be underestimated: for parts of Chilean society, the election of a communist as president was fundamentally inconceivable. Jara’s assurance that she would suspend her party membership in the event of an election victory was ultimately unable to dispel these deep-seated reservations. The mistrust ran deeper than any tactical gesture.

Fear as political currency

In the final days, the election campaign culminated in a political farce. For fear of alienating voters from the centre and the moderate right, Jara adopted some right-wing narratives. Kast, on the other hand, consistently avoided making concrete policy statements – also for fear of making himself vulnerable. His success is based less on a convincing vision for the future than on the systematic mobilisation of fear: fear of crime, fear of migration, fear of economic decline.

These threat scenarios were often exaggerated, sometimes backed up with false figures and images. But in a society that increasingly perceives itself as insecure and vulnerable, reality no longer prevailed over sentiment. Fear became political currency, and Kast became its most successful trader. What Chile can now expect in concrete terms remains unclear. Kast announced ‘big steps’ and presented catchy slogans for combating crime and migration and reducing the size of the state, but failed to provide answers as to how these policies would be implemented. Even at his final rally, he contented himself with the cryptic announcement that people would be surprised from 11 March onwards.

Reconciliation in tone, toughness in agenda. How all this will fit together in the end remains to be seen.

In his victory speech, he then struck a more conciliatory tone, spoke of the lack of ‘magic solutions’ and announced a government with broad parliamentary support. At the same time, he promised his economically liberal core constituency rapid corporate tax cuts and called on Chileans to roll up their sleeves and treat each other with respect.

Reconciliation in tone, toughness in agenda. How all this will fit together in the end remains to be seen. Kast does not have his own majority in Congress. He is dependent on the support of the conventional right, the extreme right around Johannes Kaiser and other MPs. This forces him to negotiate and, at the same time, opens up scope for political radicalisation.

His style of government could range between various authoritarian models: tactically moderate like Giorgia Meloni, disruptive like Javier Milei or repressive like Nayib Bukele. More likely is an opportunistic mixture adapted to what the Chilean context allows and what the political situation dictates. The strength and unity of the opposition will also be decisive in this regard.

This is precisely where the next major uncertainty lies. No sooner had the results been announced than recriminations began in the progressive camp. The Socialists blame the government, the Communist Party is grappling with the question of leadership, and Jara’s political future is uncertain. The question of a new leader for the entire camp – outgoing President Boric or someone else – also remains unresolved.

The left must take security and migration seriously without dehumanising them.

This trial by fire comes at an inopportune moment. More than ever, Chile needs a united, constructive opposition that clearly defines its role, formulates common guidelines and defends them. Not destructive, but credible. The lesson of this election is clear: in the race for ‘tougher’ politics, the originals always win – those who are willing to sacrifice human rights and democratic principles. Those who adopt the rhetoric of the right ultimately strengthen the right. A progressive alternative cannot consist of copying right-wing narratives. It must take a different approach.

The left must take security and migration seriously without dehumanising them. It must combine order and freedom. Above all, however, it must counter fear with political clarity, social empathy and credible hope for change. This requires a self-critical but united realignment of progressive forces. Not in the form of internal reckoning, but as a joint political project that learns from defeat and provides contemporary, credible answers to the real challenges of today. Because one thing is clear: without substantive renewal, there will be no political comeback. And this is the only way to prevent the victory of fear from becoming a permanent state of affairs.