The UK is in the midst of the most important general election in a generation. The result will define the country for years, perhaps decades, to come. On one side stands Boris Johnson, backed by far-right figures like Nigel Farage and Tommy Robinson, promising a hard Brexit and alignment with Trump’s America. On the other stands Jeremy Corbyn, at the head of a Labour party putting forward a radical platform to transform the economy. The choice could hardly be starker.

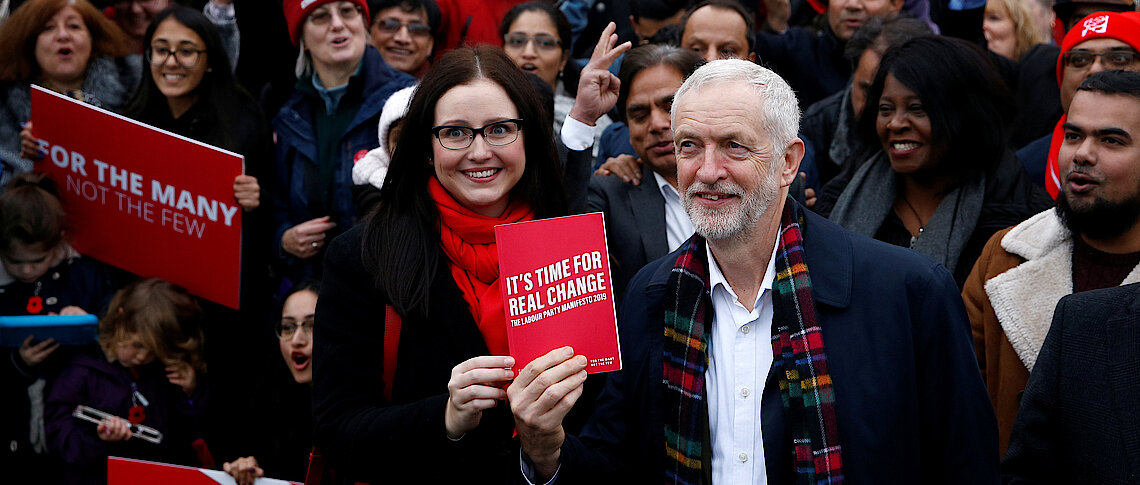

Labour’s manifesto, published on 21 November 2019, builds on the 2017 manifesto that rocked the political establishment by helping Labour to defy expectations at the polls. Back then, policies like public ownership of railways, water and energy were ridiculed by the media but turned out to be overwhelmingly popular – especially among the young. This time around, the polls suggest that Labour again has a mountain to climb if it hopes to pull off the same feat. But whether Labour wins or loses, this second manifesto under Corbyn may yet become a defining document for those seeking to shape a new consensus beyond neoliberalism. The two and a half years since the 2017 election have not been wasted: this is a deeper, more sophisticated and more radical set of policies than the one that came before.

Like in 2017, the British establishment is once again working hard to dismiss Labour’s spending plans as fantasy economics or a return to the 1970s. But the real story of Labour’s manifesto does not lie in its fiscal policy, which is scarcely out of line with many major European economies. Rather, it lies in the fruition of sustained policy development work in partnership with left-wing intellectuals and social movements. The question it seeks to answer is: how can we build a democratic and sustainable economy?

Finance for the many

For perhaps the first time in the party’s history, tackling the climate emergency is being placed at the heart of Labour’s programme, with plans for a ‘green industrial revolution’ to decarbonise the economy and create hundreds of thousands of green jobs. So far, so necessary. But Labour is promising more than a massive increase in investment. Its true radicalism lies in how this investment would be delivered. The aim is to radically democratise and decentralise the British economy through new public and co-operatively owned institutions. Thinkers Joe Guinan and Martin O’Neill have dubbed this Labour’s ‘institutional turn’.

For instance, Labour has committed to establish a new public banking system, with a National Investment Bank supported by a localised Post Bank network offering basic banking services and small business loans. (Full disclosure: I worked on a recent report for the party which developed these proposals.)

The UK left would therefore benefit greatly from more sustained international dialogue with European progressives, in order to understand the limitations of these models and the latest thinking on how they can be improved.

The party is also beginning to think about new approaches to monetary policy and regulation which can shape the credit creation of private banks in socially and ecologically beneficial ways. This is the most coherent, potentially transformative approach to banking and finance offered by any British political party in my lifetime. Ten years after the financial crisis, it offers a response to the UK’s key economic malaise: a bloated, speculative City of London which fails to invest in productive and sustainable activity.

For Labour’s international allies, it is worth noting that much of this policy platform has been inspired by continental Europe. For instance, the German public banking system has been an explicit role model for the development of Labour policy in this area. The same is true of plans to boost municipal and community ownership of energy. This builds on the German ‘Energiewende’ and the success of countries like Denmark in promoting decentralised, democratic renewable energy. To some extent, therefore, a Labour victory would simply mean the UK rejoining the European social-democratic mainstream. For the poster child of neoliberalism, this would be no small achievement.

A more democratic economy for the 21st century

Our aspirations as a movement, however, stretch further. The UK left would therefore benefit greatly from more sustained international dialogue with European progressives, in order to understand the limitations of these models and the latest thinking on how they can be improved.

One way Labour is trying to do this is by extending the principles of democratic ownership and control of key infrastructure into new areas. The party’s flagship policy to roll out universal free public broadband is a case in point. It is not simply a shiny election giveaway, but has been chosen to represent the party’s core offer: to democratise the economy whilst also modernising it. Labour wishes to counter the accusation that it is harking back to a vanished past and instead reinvent democratic socialism for the future. This means asking: what are the ‘commanding heights’ of today’s economy? Just as the railways and waterways were the critical infrastructure of the 19th century, so the internet and the banking system are the critical infrastructure of the 21st. Finding new ways to collectivise control of these systems is key to the Corbynite political project.

Ultimately, what’s most exciting about Labour’s 2019 manifesto is not what’s in it, but what sits behind it.

Labour is also moving beyond an expansion of public ownership to thinking more deeply about how to democratise the private sector. Its approach to this problem can be summed up in three flagship policies. First, the proposal to require large companies to transfer shares into ‘Inclusive Ownership Funds’ controlled collectively by their workers. This is inspired by the Swedish Meidner Plan and aims to facilitate a gradual transition from shareholder capitalism to employee ownership. Second, a new Co-operative Development Agency with a mission to double the size of the co-operative sector. Third, promoting ‘community wealth building’ – an approach pioneered by Preston City Council to keep public money circulating in the local economy by supporting local and community-owned businesses.

A more democratic party

Finally, mention must go to the party’s promise to phase in a four-day working week by 2030 – perhaps one of its most radical pledges of all. With this, Labour hopes to become the heir of previous struggles to limit working hours, such as the fight for an eight-hour day or paid holidays. A shorter working week has long been advocated by radical left thinkers from many perspectives. Environmentalists believe it could help tackle the ecological crisis by using improvements in productivity to expand leisure time rather than to expand economic activity. Feminists hope it would help to equalise and value domestic labour and care work.

Along with moves towards ‘universal basic services’ (such as free buses, childcare and broadband) this reflects a key strand of Labour’s thinking. It aims not only to democratise the market economy by expanding public and co-operative ownership, but also to restrict the reach of the market economy by expanding our ability to meet our needs outside it.

Ultimately, what’s most exciting about Labour’s 2019 manifesto is not what’s in it, but what sits behind it. Policies on issues ranging from rent control to access to medicines have been adopted directly from social movements and campaigns. The Labour membership has taken the lead in pushing the party’s policy further at its annual conference – from extending free movement to abolishing private schools. Policy reports have been commissioned from some of the leading thinkers on the UK left, such as ‘Land for the Many’, which sets out a vision to radically democratise the ownership and use of land.

Not all of this has made its way into the manifesto. But it indicates a depth of thinking and mobilisation on the UK left that simply did not exist even two years ago. Whatever the result of the election, this offers hope. A new political settlement is being shaped from the bottom up: Corbynism’s early promise to democratise politics within the labour movement is being fulfilled. We can only hope it will be able to do the same for the UK.