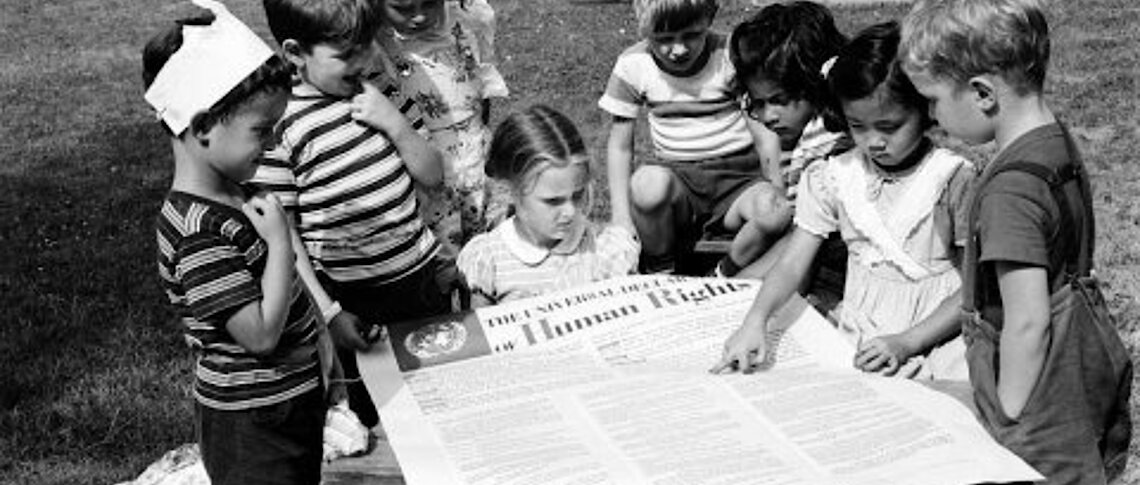

At the end of this year the world will mark a significant anniversary. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), that landmark UN charter aimed at resetting the dial on human and state relations, will be 70 years old. In theory it represents the minimal norms of all liberal democracies, everywhere.

Yet just a few weeks ago the renowned Chinese artist and activist, Ai Weiwei, remarked that ‘the West has all but abandoned its…support for the precious ideals contained in declarations on universal rights.’ Is he correct?

The abject failure of the international community (and in particular, the limp League of Nations, the UN’s precursor) to prevent crimes against humanity, and ultimately genocide, at the heart of supposedly democratic Europe-despite the writing on the wall for over a decade- was one of the key drivers behind the campaign by multiple NGOs for the nascent United Nations to adopt an international bill of rights.

Cornerstone of modern human rights law

Some were bitterly disappointed when a declaration, rather than a legally binding treaty, was drafted by the UN’s Commission on Human Rights, chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt, who worked alongside a mosaic of delegates from different cultures and nations.

What these critics could not have known then is that the UDHR would become the procreator of modern international human rights law, parenting an array of treaties which are legally binding. These encompass economic, social and cultural rights alongside civil and political liberties and span a host of regional treaties in Africa, the Americas and Europe (including the European Convention on Human Rights). Virtually all of them, including single issue instruments ranging from torture to children’s rights, acknowledge their UDHR parentage in their preambles.

Human rights are not a euphemism for legal rights but a means of influencing them.

Many of these charters have increased the scope of the declaration, encompassing new struggles and insights whilst correcting deficiencies which reflected the era the UDHR was drafted in. The whole of sub-Saharan Africa was still subject to colonial rule in 1948, but today it is human rights activism in the global South which has driven many of these advances.

Most of us take this international human rights architecture for granted, but just 70 years ago there were no internationally recognised human rights standards to cite in political struggles, let alone human rights courts, or committees, where individuals could hold their own governments to account.

Yet the crucially important legal recognition of universal human rights norms has undoubtedly come at a price. Human rights are not a euphemism for legal rights but a means of influencing them. But for too many people human rights are understood only as the last legal case they’ve read about, obscuring the ‘big idea’ the UDHR drafters were intent on shaping.

It was lessons learnt from a catastrophic world war and genocide – referenced in the preamble as ‘barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind’ –which drove the ethical vision of the UDHR. This can be distilled into 3 simple assertions that (you might think) are ever more relevant in today’s world.

1) That liberty without the economic wherewithal to live a dignified life is no freedom at all, but a ‘larger freedom’ involving ‘social progress and better standards of living’ is essential for human dignity.

2) That if democracies are not to crumble into ethno-nationalist tyrannies, a system of accountability to a higher set of norms and institutions must moderate national sovereignty and majority rule.

3) That when the chips are down, and life and liberty are at stake, humanity should always trump nationality.

A document for our times

This world-view was not intended as an alternative ideology to other political, secular or religious philosophies, but as a bottom line set of norms and standards, enabling diverse communities and nations to live together in mutual respect and peace.

Yet in the thirty years I have been studying and writing about human rights, I can remember no period when we’ve been in greater danger of losing the insights and wisdom of the UDHR and the legal framework it spawned.

Western democracies, like other states, have frequently abused human rights, of course, whilst valuing them as a means by which the West can judge the rest.

But there has never been a time since 1948 when states which once claimed to champion the UDHR have so fiercely articulated a world-view and mind –set that directly or indirectly undermines its basic value system.

Whilst the world holds its breath as Donald Trump puts ‘America first ‘ and finds an equivalence between neo-Nazis and their opponents in the USA, Europe waits apprehensively to discover whether, after withdrawing from the EU Human Rights Charter, the UK has the European Court of Human Rights in its sites next.

Strongmen rulers who acknowledge few higher norms than the greatness of their own state compete for influence, as the epicentre of world power shifts inexorably towards China and Russia, whose government s don’t pretended to value human rights; even hypocritically.

Within Europe, anti-Muslim ethno-nationalism and virulent anti-migrant sentiments are resurgent in many states. In Germany this is often linked to Angela Merkel’s exceptional act of receiving over one million asylum seekers. But this ‘new nationalism’ and ‘nativism’ have also gripped European countries which have accepted almost no refugees, suggesting leadership and ideology are crucial factors in increasing xenophobia.

The UDHR was not written for the past, for that was already over and could not be undone.

These shifts have been a long time in the making. As others have remarked, they appear driven mainly by a popular backlash against the grotesque inequalities and marginalisation of communities ‘left behind’ by globalisation, ruthlessly exploited by those who have benefitted the most from it.

This is not to imply we are reliving the precise conditions that led to the human rights renaissance after WW2. That is not the point. The UDHR was not written for the past, for that was already over and could not be undone.

It was written for a moment like now; to equip us to recognise when forgetfulness returns, as the drafters knew it surely would, and lessons learnt from genocide and war are replaced by a new narrowing of the horizon, as national pride and international indifference re-emerge in fresh forms.

As ‘us and them’ increasingly replace ‘we and everyone,’ as human rights norms are once again presented as a threat to ‘national sovereignty,’ the danger is not that the UDHR will be overturned or ridiculed in some future late night tweet.

The greater threat is that international norms of solidarity and humanity which the ‘barbarous acts’ gave expression to in the form of the UDHR will simply be forgotten; will wither away from lack of use and application.

The ‘cosmopolitan norm’ (so-called) heralded by the UDHR was not aimed at diluting citizenship of individual states or national identity. It simply affirmed that we are ‘all members of the human family,’ as the very first sentence of the Preamble puts it, providing a bottom line obligation on the global community to protect us when our own governments won’t.

Or as Ai Weiwei recently remarked when surveying the current state of our world: ‘establishing and understanding that we all belong to one humanity is the most essential step for how we might continue to exist on this sphere we call earth.’