During his final term in office, President Barack Obama emphasised that the focus of US security and economic policy would be on the Indo-Pacific region. There were two important reasons for this change in strategy: first, the need to control the rise of China as a global superpower and the expansion of its economic and military influence in the region. And second, the recognition of the Indo-Pacific region as a bloc with strong economic dynamics and great importance for the future international order.

The actual term ‘Indo-Pacific’ was subsequently introduced by former US President Donald Trump, referring to it as the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP) to counter China’s growing economic and political influence in the region and to defend the so-called rules-based international order.

Developments in the Indo-Pacific are set to dominate global public and media attention in the coming years, including the formation of regional blocs and possible political-military and, above all, economic conflicts of interest. In this way, the EU, the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, India and China all seek to play a decisive and active role in shaping developments in this dynamic region.

Two intertwined free trade zones

One of the most important determinants of the increased interest in this region is the implementation of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which was signed on 15 November 2020 at the ASEAN virtual summit in Hanoi. By definition, RCEP is a free trade agreement with the aim of removing protectionist barriers to trade between member countries. The members of RCEP include Brunei, Indonesia, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand. Following clashes with China in the Himalayas in 2020, New Delhi was forced to rethink its foreign policy and now seems more willing to join the front against China with the United States and other democratic states. Thus, it is currently difficult for India to join a free trade agreement that includes China.

On the other side, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP or TPP) was Obama’s most important trade agreement with other Indo-Pacific countries, marking Washington’s return to the region. China was not included in this agreement. In 2017, however, the Trump administration unexpectedly withdrew from the TPP. So far, the UK is the only additional country to have formally applied to join the TPP, which now counts 12 members.

As a result of all these developments, two intertwined free trade zones have formed in the Indo-Pacific region. This means that, over time, the countries of the region can move from one bloc to the other, considering the economic advantages offered by these forms of regional cooperation, and that these two separate entities could transform into a single free trade area.

A region of conflicts of interest

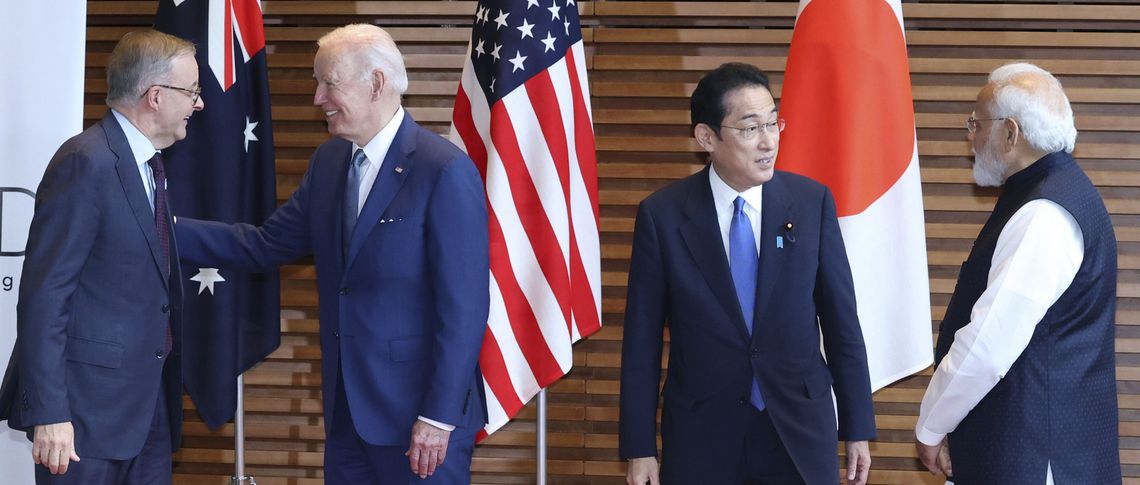

Washington, because of its historical ties, plans to create an expanded regional economic, political and military bloc in the Indo-Pacific. As a first step, The QUAD States, a group of four countries – the US, Japan, India and Australia – held a meeting in March 2021, agreeing to collaborate on climate, health and technology. In September 2021, the leaders of Australia, the UK and the US announced plans to establish an enhanced trilateral Security Partnership, known as AUKUS, which builds on the longstanding and ongoing bilateral relationships and aims to strengthen the ability of each government to support security and defence interests in the region.

The United States has long viewed the Indo-Pacific region as critical to its security and prosperity. On 11 February 2022, the White House announced a new program for a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific region’, pledging support for regional connectivity, trade and investment, and deepening bilateral and multilateral partnerships.

The Chinese leadership wants to create the impression that China’s rise is inevitable.

The new connectivity initiative, the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), which was unveiled at the G20 Summit in New Delhi in 2023, shows the extent to which India is now being courted by the West as a partner to counterbalance China. It is seen as an alternative to China’s Silk Road Initiative by its initiators — the United States, India, the European Union, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Italy, Germany and France. The European Union and India resumed free trade agreement negotiations in summer 2022 to deepen their strategic partnership.

China – a country that goes its own way and at its own pace – considers the IMEC, TPP, QUAD, and AUKUS agreements as a bloc forming against it. On the one hand, China’s Indo-Pacific strategy is pragmatic: its motto in the region: ‘Let’s grow together’, shows its desire to build economic cooperation first and foremost while pursuing a peaceful foreign policy rather than using military force. On the other hand, the Chinese leadership wants to create the impression that China’s rise is inevitable and that countries will have to decide whether they want to be integrated into its economic system because of its huge market and the official reserves held by the Chinese Central Bank. Meanwhile, many of China’s neighbours want US involvement in the Indo-Pacific region so that they do not become solely dependent on China.

What about Europe?

On 19 April 2021, the European Union adopted its long-awaited strategy for the Indo-Pacific region, officially called the ‘EU Strategy for Indo-Pacific Cooperation’. The Council conclusions represent a balanced effort by the 27 European countries to formulate a common position in the evolving debate on the Indo-Pacific. Through this new strategy and the Global Gateway, the EU aims to contribute to stability, security, prosperity and sustainable development in the region in accordance with the principles of democracy, the rule of law and human rights.

The EU gives priority to its economic interests in its relations with the countries of the Indo-Pacific region, and, accordingly, China occupies a very important place in these relations. Moreover, from a geo-economic point of view, Europe counts the Indo-Pacific region among its most important foreign trade partners, including Japan, India, South Korea, Australia and South-East Asian countries, which are developing rapidly in economic terms.

China lies at the heart of the German Indo-Pacific strategy and of its economic relations in the Indo-Pacific.

The first important question for Brussels is whether the EU’s 27 members can agree to pursue the Indo-Pacific Strategy with determination and implement it in a coherent way. If the EU is unable to agree on a common and unified policy for the Indo-Pacific, then each country will pursue a policy that prioritises its own national interests. The superpower struggle between China and the United States could force countries in the region, especially EU members, into a choice between the two powers.

Germany in particular, due to its export-oriented economic structure, would like to further develop its economic relations with the countries of this region. Clearly, China lies at the heart of the German Indo-Pacific strategy and of its economic relations in the Indo-Pacific.

A careful examination of the strategic statements made by Berlin and Brussels regarding the Indo-Pacific suggests that the EU/Germany will pursue a two-track approach with regard to China and the Indo-Pacific countries. On the one hand, they want to show solidarity with Washington by sharing the US position on ‘respect for human rights, fundamental freedoms, the rule of law, the protection of minorities in Xinjiang and Tibet and autonomy in Hong Kong’. On the other hand, Germany’s dual strategy suggests that the German government and business community will continue to improve and deepen bilateral economic relations with China and other Indo-Pacific countries in the coming years. An important question at this point is how Berlin can reconcile its strong economic interests with pressuring Beijing and the region’s authoritarian regimes to implement ‘democratic values’?