Conspiracy theories ran wild during the 2016 American presidential election. According to one theory, rival candidate Hillary Clinton was going to rig the election with the help of the biased media. According to another long-standing theory that re-surfaced at the time, Barack Obama was not a legitimate president because he was born in Kenya. Perhaps the most elaborate conspiracy theory was “pizzagate” involving allegations that Hillary Clinton and other prominent Democrats were involved in a secret paedophile ring run from a Washington DC pizza restaurant. The most prominent supporter of these conspiracy theories was none other than Donald Trump, and he used conspiracy theories so much that he became known as the “conspiracy candidate”. Even since he won the election he has been making regular allegations of conspiracy—most recently that he was the target of a wire-tapping campaign authorised by Obama during the 2016 presidential race.

The prominence of conspiracy theories during the US election campaign was echoed elsewhere too. For example, conspiracy theories were a major feature of the 2016 EU referendum in the UK. Politicians who changed camps during the campaign were alleged to be “sleepers” for the Remain side. The voter registration website crash was apparently set up by the Remain campaign so that they could enrol more voters. Polling cards were allegedly being sent to non-British citizens to increase the vote for Remain. Whilst it is, of course, commonplace for politicians to score points off each other using rumours and gossip, 2016 saw an unprecedented turn to conspiracy theories and this raises an important question—do conspiracy theories have an effect on people’s attitudes that might be enough to sway their vote?

Whilst it is commonplace for politicians to score points off each other using rumours and gossip, 2016 saw an unprecedented turn to conspiracy theories

Recent experimental findings suggest that exposure to conspiracy theories may indeed change the way people think about social issues. For example, one study showed that people believed conspiracy theories about the Death of Princess Diana more after reading unsubstantiated conspiracy-related material, but that they were unaware that their attitudes had changed. In other words, the unfounded conspiracy theories changed their minds about the causes of the death of Princess Diana without them knowing about it. This points to the potential for conspiracy theories to have an insidious effect on people’s attitudes and behaviours.

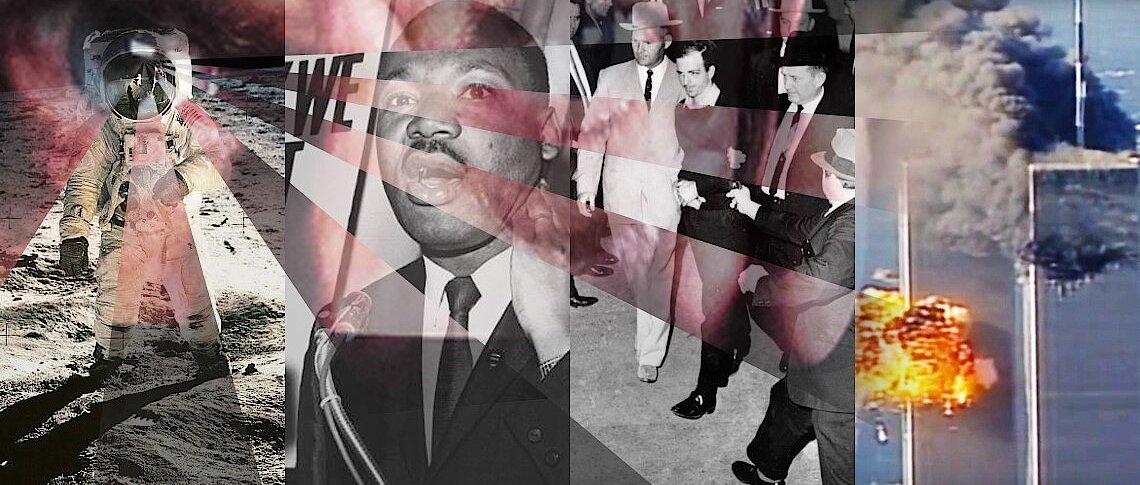

Other research has focused more specifically on the effects of conspiracy theories on political intentions. In one study, people were presented with conspiracy theories about the government being involved in shady plots and schemes (e.g., that the British government assassinated Princess Diana; that the 9/11 attacks were orchestrated by the US government), and were asked about their voting intentions in an upcoming election. Findings showed that compared to a condition where participants were given anti-conspiracy material to read instead, the conspiracy theories reduced people’s intentions to vote. More specifically, people felt less inclined to vote because the conspiracy theories made them feel politically powerless. Other studies using similar methods have shown that conspiracy theories also reduce people’s engagement with climate change, vaccination and the workplace.

The two important messages from this emerging research are that conspiracy theories seem to reduce engagement with important social systems like the government and make people feel powerless or that their actions would make no difference. In some of these studies, conspiracy theories also made people feel uncertain and disillusioned. Therefore rather than empowering people to stand up and act on perceived injustices, conspiracy theories appear to make them disengage and instead do nothing. They seem to erode trust in politicians and institutions and lead to apathy rather than action. Why would people want to vote for a political system that they think is constantly committing crimes and hiding information from the public?

Rather than empowering people to stand up and act on perceived injustices, conspiracy theories appear to make them disengage and instead do nothing.

But people might have other options to deal with these perceived injustices. For example, if they do not want to vote for a system that they perceive to be unfair, they can instead engage in non-normative action, or action intended to change the system. One study in the aftermath of the Fukushima catastrophe showed that a general tendency to endorse conspiracy theories—independent of their content—was linked to intentions to engage in individual protest (e.g., changing the energy supplier to renewable energies), normative collective protest (e.g., participating in a demonstration), and non-normative collective protest (e.g., blocking rail tracks of a nuclear waste transport in an act of civil disobedience). Perhaps, therefore, conspiracy theories might reduce intentions to act politically in support of what is seen as a corrupt system but increase the tendency to change the status quo by other means that directly challenge the system. More research is required to understand when conspiracy theories are likely to lead to apathy, and when they are likely to promote action to change the system.

Another important question remains about the role of conspiracy theories in politics. Specifically, is it possible that politicians deliberately use conspiracy theories as a way to win or maintain power? It would certainly appear they have some knowledge of conspiracy theories’ power to change people’s attitudes. Going back to the example of Donald Trump during the US election, his consistent use of conspiracy theories would suggest that he was using them deliberately to manipulate voters. He regularly peddled ideas that would resonate with the suspicious among ordinary people (e.g., that Obama and his administration did not want to fight terrorism; or that they were actually aiding ISIS). Although it is difficult to know if this use of conspiracy theories is deliberate, it is clear that 2016 was a pivotal year in politics and at the same time that it was riddled with political conspiracy theories. Whether or not politicians use conspiracy theories as tools to increase their votes, or to keep the masses under control by reducing their vigilance and political engagement, remains an important question for future research.